We Are What We Stand On, The Socio-Aesthetic Society

Chapters

Justus Jorgensen and Montsalvat

Metamorphosis of The Middle Class

Beginning of the Mud Brick Revival

Professional mud brick building

Aims, Objectives, and Spiritual Conflicts

The Tarnagulla-DunollyMoliagul Triangle

Mud Brick Builders of Colour, Culture and Accomplishment

The Renaissance of the Australian Film Industry

The Impact of the Environment on the Eltham Inhabitants

The Impact of the Eltham Inhabitants on the Environment

The Rediscovery of the Indigenous Landscape

The Socio-Aesthetic Society

Author: Alistair Knox

Tim Burstall's connection with Eltham extended back to 1946. He worked on the repairs to the Brocksopp House, which was in those days known as Souter's Cottage. A couple of years later, he was one of a group who decided to buy land in the district. Over a short period, Tim, who was to become a film director, and his wife, Betty, Brian O'Shaughnessy, the philosopher, Frank Kellaway, the poet, Arthur Boyd and John Perceval, the painters, Peter and Lottie Glow, Ray and Betty Marginson, Freddie and his wife Verna, among others, bought land adjacent to each other on the Panorama Heights Estate near the big dam at the end of Napier Crescent. The Jackas also brought a caravan on to the site and placed it on an area of concrete paving which was all that remained of an old dairy which has been the original building on that land. The moment Tim paid a deposit on his land it was inevitable that he would cause an influx of people into Eltham. He had always been a catalyst for new ideas and would form a strong strand in the mud brick cordon that was encircling Eltham. He seemed to know a great number of university and artistic personalities. His gregarious nature caused him to be the party-goer par excellence.

He was fascinated in all forms of social interchange and was wonderfully free with invitations to his establishment from the first moment there was any form of shelter to make an invitation possible. His gracious and handsome wife, Betty, was an ideal foil for his social activities. Not only did she go along with much of it by nature, but she always had a dynamic energy and tremendous ideas. Betty was the epitomy of those women who stand behind successful men. Her two young children, Dan and Tom, were to keep her from taking a paid job, but she worked at the house she and Tim were building with the industry and ability that was becoming a hallmark of many of the girls and wives who came to the tensile Eltham bushland to carve out habitations for themselves and their families.

There were several places in the district where voices could be heard issuing from areas of enclosed bushland. It was impossible to see the speakers until you walked through an opening in the trees into a cleared space. Inevitably, mud bricks, excavations and buildings would be in progress within it. Tim was never happier than when he was inviting people home to his embryonic house. He rarely consulted Betty. She seemed to know by instinct that a group would generally materialize when Tim returned from the pub on a Saturday night, if they were not planning to go out themselves. Even ifthey were visiting others, people would still tend to return home with Tim and go along with them to where they were visiting. Eltham society was extraordinarily open in the late 40s.

One recent Saturday afternoon Tim called to our house and we had a recollective conversation. It was more a monologue by him setting out his times and activities in the Eltham community. He prefixed many remarks by saying 'Do you remember?' .... 'how our house was like the common room on that side of the creek?' Every night people gathered and there was a fire and the lamps were lit. (We did not have electric power until about 1956.)

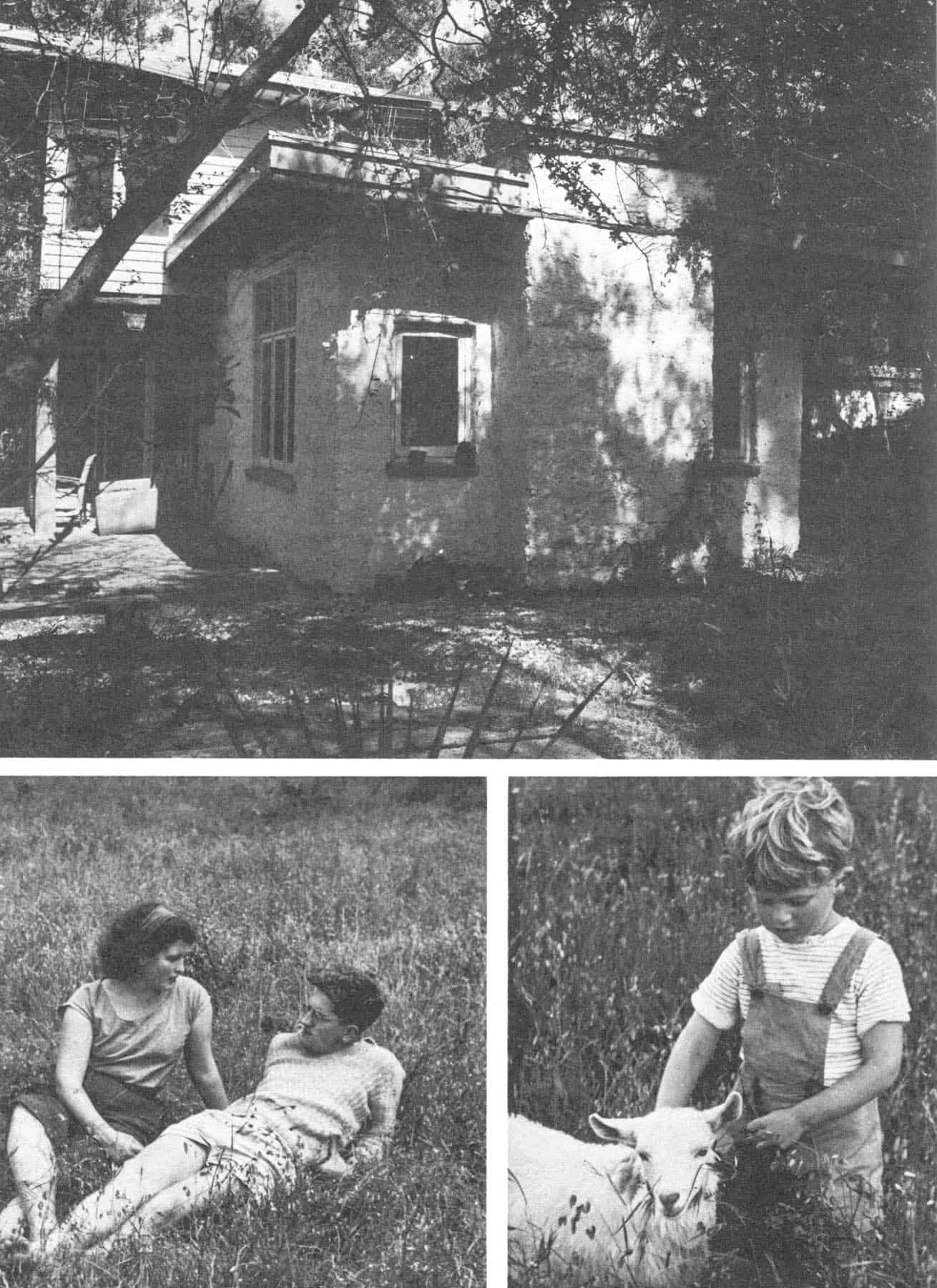

Above top: A view of the Burstall house 1980.

Above bottom left: Above bottom right: Tim and Betty Burstall discussing their building project 1950.

Above top: A view of the Burstall house 1980.

Above bottom left: Above bottom right: Tim and Betty Burstall discussing their building project 1950.

Their son, Tom, 1956

I thought of Betty-strong, young, beautiful, cooking at the one-fire stove while we men and sundry wives and girl friends sat around the open fire and talked. Betty's curly brown hair, athletic figure, good mind, handsome face and enduring capacity for creative domesticity would contribute to the conversation as the cooking proceeded. Eventually, we would sit down to a superb meal which seemed to last until it was time to go home. We were halfaware that it was getting towards midnight when Betty would rise from her seat and go to the old-fashioned coffee grinder on the wall and crank it at a great rate to fill the room with the smell of the fresh ground beans.

There was a strange contrast between the sophisticated talk inside the partly-finished house and the quiet of the night when we went outside to go home. The luminous Eltham stars shed a ghostly light over the valley, which could be clearly seen from the doorway before the regenerating bush growth was able to obscure it. It can never be accurately estimated what part the natural environment played in the post-war history of the district, but we were all certain that most of it would never have happened if the action had been located in a mundane or semi-suburban landscape.

Tim continued his story: 'In 1946, Eltham was still small enough for everyone to know everyone else. Do you remember the Danilia Vassilief party when you still lived in Heidelberg? It would have been in 1947. 'We all went up in Arthur Boyd's car. Do you know how many set out to return home in it? You will remember we gathered new passengers at the party.' 'It was the fullest car I ever travelled in' , I answered. Tim swore unequivocably that there were 25 souls on board when we set off for home.

Danilia Vassilief was a really outstanding artist and personality. He came to Australia after the Russian Revolution, where he had been a Cossack officer in the White Russian Army. Among his feats of prowess in the land of his adoption was the building of some nine miles of railway in a remote northern area. He subsequently became an art teacher at the Koornong Experimental School in North Warrandyte. Some years after its closure, he transferred as art teacher to the Eltham High School, and stayed there until he died during the 50s. Near the end of his life, he lived in the caretaker's cottage attached to the school.

He was a remarkable and colourful figure and a major influence on men like Sid Nolan, Arthur Boyd and John Perceval. He was older and more experienced and international and had all the capacities of a great visual artist. He specialised in both painting and sculpture. His house in North Warrandyte, called 'Stonygrad' was in essence a total sculpting. It had two periods of growth. At this time his intense Cossack nature was digging deeper and more passionately into the basement of his building. It was in the centre of the house. He had dug a hole in the stone foundation to make a small underground room that became more constricting the deeper you went as though the walls sloped slightly inwards. There was not much light in the house on the night of the party and people seemed to be crammed everywhere into smallish alcoves and spaces hewn out of the stone walls.

I remember struggling aboard the Boyd car after the party. It was crowded beyond belief. The canvas roof was folded down and we all stood up and clung to each other and on to the sides of the car as we headed off down the bush track. There was a distinct sense of it being top-heavy. I t was about 1924 model Dodge that had lain idle and useless in the Boyd backyard at Wahroonga Crescent, Murrumbeena for years during the war. No one thought it could go. It was little better than a repository for rubbish. One day Arthur tinkered with it a bit, did a few things and it suddenly started up. Flocks of amazed birds and other living things flew out of it as its pulsating rhythm disturbed them. It became rapidly socially elevated into a noble and necessary appendage to the Boyd menage in an almost car-less world.

It had a grave dignity and a patient heroic nature that went with its long history. It was kept going by all sorts of improvisations and strategems. Chewing gum sealed petrol leaks, silver paper connected electrical breakdowns and on one occasion in those days of scarcity, when tyres could not be purchased, one wheel was without a tube at all. The Boyd's wanted to make a journey, so they filled the outer tyre with cow manure so that it could move along the road without actually running on the rim! It performed a great social coagulating job for all concerned.

The beautiful moonlight nights of Warrandyte and Eltham are without equal anywhere and as we left for home we were all exhilarated with the prospect of a whirl through the overhanging branches and on into the first streaks of dawn. David Boyd, Arthur's dashing younger brother, who looked like a young Lord Byron, was crouched over the wheel trying to extract some more speed out of the vehicle when the inevitable happened. A tyre burst with a resounding explosion and the car zig-zagged violently and should have overturned. I suppose some of us owed our lives to David's inspired driving that night.

We clambered out and did the only thing possible: we left the car where it was and started walking towards our house in Mosman Drive, Eaglemont. As the sun rose, the scene resembled a miniature retreat from Moscow. The line of people were spread out for about a mile by the time we reached Banksia Street. Finally, we arrived at our house around 9 a.m. and rested for two or three hours. But in those days rest was a secondary matter to enjoyment: we roused ourselves and got up to play charades until late in the night.

Tim continued to recount how the whole Eltham community appeared to gather on Saturday at midday at the garden of the Eltham Hotel. Sometimes the numbers rose to forty or more. They would include Arthur Munday from Montsalvat (who had given up his solicitor's practice to run a vegetable round in the district); Ken and Denise Pittendrigh, who purchased the Harcourt house next to the creek; Joy and Harry Jobbins who bought 'Shoestring' and extended it; Kath and Ken Guest, who owned the original 'Laughing Waters', John and Faye Harcourt, Mac and Katrine Ball, Hans and Leila Hohne, Tim and Betty Burstall, Eric Ward, Peter Glass, Tom Sanders, Gordon and Pauline Ford, Bill and Gwen Peck, Matcham Skipper, John and Marj McClelland and John Clendinnen-to name but a section of the locals that came readily to his mind.

The chief topic of conversation on these mid-day meetings was mud bricks and building. Labour was virtually unobtainable and the odd people offering for work were skittish and hard to hold. Labour was an absorbing topic of conversation. We were a close knit community and spent most of our time with each other. Tim explained how Horrie Judd really spoiled the building scene for him. 'It was an idyllic world working for you, Al, until Horrie Judd came along', he said.

It was a time of freedom and dreaming, a background to an emancipated way of living. Horrie had a stake in the success of the building company. He was conscientiousness itself. He wanted us to really work hard. We all admired him for his tremendous ability in making mud bricks and producing results. He could nearly double anyone else's production rate. He thought Gordon could make a reasonable worker, but clearly realised that I had no intention of earning a living at it. He tried to separate Gordon and me from each other because we were always laughing and exchanging existentialist jokes.' Tim then explained how Betty and he built their first house for less than £600.

Betty Burstall was the first self-sufficiency activist in the district. She kept geese, goats, tanned hides, built the house, brought up the children and did a wide variety of Herculean tasks including tidying up after everyone generally. Later, when there was more time, she also played a good game of tennis and this became the weekend afternoon activity at our old house in York Street. The most spectacular player was my first son Tony, who was capable of serving four successive double 'faults at great speed in one game and who would then hurl the racquet after the ball across the gravel court. A couple of months of this activity produced a variety of broken racquets around the place. It is a far cry from the Tony of today-mine host of Mietta's, the elegant restaurant he and Mietta own in Brunswick Street, North Fitzroy. He has been transformed into a gracious personality who would never break a racquet and be careful to never serve more than two successive doubles, no matter how he felt.

'We moved into our house in 1950 after I spent a year in Canberra' Tim continued, 'and settled down to helping the Eltham community to become the socio-aesthetic centre of Melbourne. Everyone of us thought we could build a house or do just about anything if we really set our minds to it. Nothing seemed to be impossible, because we were still improvising and using what we had. There seemed to be no idea that we had to go and buy new materials to build or do any other thing. As we meditated as to who was coming to live in Eltham at this period, or who were regular visitors, we realised that nearly every important painter, with the exception of Sid Nolan, who had gone overseas after marrying Cynthia Reid some time earlier, had been involved in our community at one time or another.'

They made up part of the Eltham scene and were deeply influenced by the bush and the landscape. There were the'painters, Arthur Boyd, David Boyd, John Perceval, Charlie Blackman, Ian Syme, Clifton Pugh, Len French and many others. The actors included Barry Humphries, Peter O'Shaughnessy and Wynn Roberts. Among the philosophers were David Armstrong, Don Gunner and "Cammo" Jackson.' 'It was a rural Bloomsbury', Tim explained. Nobody was allowed to become too pompous because we all preferred lifestyle to comment. A variety of discussions were generated in the Burstall house, such as Ian Syme and Cliff Pugh debating the non-figurative versus the figurative painters.

Some were drawn to Eltham through gathering at the first meeting place in the city following the war. This was 'Mr' Jorgensen's back room at the Mitre Tavern on Tuesdays and Thursdays. These gatherings were often followed by dinner at the Latin Club. The room at the Mitre was lost when it was re-modelled so the Swanston Family Hotel in Swanston Street became the meeting place on two nights each week. Friday night was the main night. I t had as much a coffee house character as that of a hotel.

Tim explained that there were men like Brian Fitzpatrick, Eric Lambert, David Armstrong, Geoff Underhill, Peter O'Shaughnessy and others at one end of the bar and at the other assembled the beginnings of a petty criminal group. This general gathering developed into what became known as the 'Drift', a loose name given to Friday night activities which started from this centre and had no explicable reason for being. They just happened because they happened.

Tim commented that, looking back on those times, the scene was like a cross between Greenwich Village in New York and Eltham. It eventually spawned a whole series of cafe theatres in Fitzroy and Carlton like the 'Last Laugh', the 'Flying Trapeze' and Tony's Sunday nights at Mietta's for a time.

Betty Burstall herself launched and ran 'La Mama' in Carlton. They produced new poets and artists and generated a new lifestyle dimension in Melbourne. The 'Drift' people would often dine at the Del Capri in Carlton. On the way from the Swanston Family they would call for a while at Bernie Lawson's studio in Collingwood and pickup men like Ian Mair and Bernard O'Dowd's son. At dinner an outing would be arranged to fill in the balance of the night. They would set off like a wedding cortege to do a quick round of two or three parties and the unsuspecting party-givers would open their front doors to be confronted with up to 40 uninvited guests. If this entertainment did not prove up to standard, there was a sign given amongst the 'Drifters' which consisted of pulling the left ear as an indication that it was time to move on to the next place of entertainment.

There were times when Barry Humphries, who was also a regular, took them down to Luna Park and they watched the occasional financially successful person who joined in suspended and flattened against the side of the rotor like a medieval victim on the wheel.

When the Swanston Family Hotel closed in the middle 50s, they chopped a hole in the floor and stuck a tree in it. They then moved off to another hotel meeting place called 'Tatts'. Tim said that the motivating force of the Drift could be described by an existentialist remark, 'Swing with the Living Moment'. The group was a kind of mad organism with life in itself. There was the night, for example, when Tim bet he could swim from McClelland's place in 'Laughing Waters' down the Yarra River to Morrison's in half an hour. Some considerable amount of alcohol had been consumed and Don Gunner, the philosopher, Tim and another man set off feeling like channel swimmers. It was only a stone's throw overland, but Tim counted 32 bends in the course of the stream before they made it hours later. They were naked and the car that had been sent to pick them up had left long before they arrived, thinking they were not coming. So, in the pre-dawn darkness, the three ghostly figures moved silently and sadly through the trees back to McClellands.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >