Alternative Housing, New Life for the Inner City

New Life for the Inner City

Author: Alistair Knox

A case study in community action

THE building industry in Australia rises to a crescendo every December. The climax precedes the five-week holiday break which starts around the twentieth of the month. Each year I try to tie up our planning in good time, provide all the necessary holiday pay and bonuses for the staff and make arrangements for a couple of weeks by the sea just after New Year. But every year the pressure seems to increase rather than grow less.

The year 1975 was no exception. Almost the first day following the Christmas break-up, when I was beginning to feel normality seeping back into my aching bones, I received a telephone call from Ron Pinnell. My relationship with Ron stretched back to the day when Barry Humphries, our local wit, satirist and actor, was just setting out on his extraordinary career. (Humphries' most famous character, whom he impersonates with diabolical glee, is named Edna Everage, now Dame Edna. She is a married lady from the suburbs of Melbourne, one of the largest and most banal middleclass areas in the world. She is full of platitudes, superficial good works, sanctimony and trite, second-rate standards.) Ron Pinnell had a melancholy voice on the phone, tinged with plaintive disillusionment and sadness, as though the worst was about to happen. He figured in the early Barry Humphries/Peter O'Shaughnessy productions as Norm Everage, Mrs Everage's unfortunate spouse. At other times he played Kennie, Mrs Everage's hopeful but rather unpleasant young son.

The intervening years did not seem to have lessened the ominous, foreboding quality of Ron's voice when he asked if he could see me right in the middle of the Christmas public holidays. It concerned South Burnley where he lived, an inner suburb being threatened with social extinction by rapacious redevelopment. I reluctantly invited him, his wife and another girl, Barbara Flynn, to visit the next day because the matter was so urgent. There were only fourteen days allowed to lodge an objection to the proposal, which had of course been advertised on the property at the outset of the holiday period in the hope that it would not be noticed in what Mrs Everage would have called 'the festive season'. The proposal was to erect another block of eighteen units rising to three storeys, including the garages underneath. It was part of an all-too-familiar pattern and by no means the developer's first application. The whole community was on the brink of social collapse through soulless unit housing spreading out like a galloping cancer in all directions.

South Burnley is immediately across the Yarra from Toorak, Melbourne's most expensive suburb. A bridge actually connects them, but some years earlier Melbourne's first inner freeway was built along the river bank, even cantilevering over it in places. When it reached South Burnley, it caused a traffic interchange because of the bridge. The resultant confluence of exits and entrances changed this residential area into a freeway ghetto. However the local community remained alive, largely because of its will-power and long-standing cohesiveness. The existing houses were mostly small and on small allotments. They were early century buildings of brick and timber, with slate or iron roof predominating. The narrow rights of way behind them were mostly bounded by rusty corrugated-iron six or seven foot fences. The lack of pretension of the community would have disappointed the residents on the south side of the river if they ever went there, but the existing inhabitants enjoyed a sense of quiet, while the area retained a human scale' and of people walking and talking within it.

Ron Pinnell and his wife, Shirley, worked hard for what they had and Barbara Flynn was a conscientious school teacher. When we met, I told them that their desire to keep their existing lifestyle depended on their personal efforts to exercise their democratic rights. The control of land use in democracy consists of argument and counter-argument. It is based on a belief in profit from land at the expense of the community. The practice in Australia is mostly the old colonial attitude of getting in first and staking a claim. The development of the claim may devastate the land, but the claimant just moves off with his spoils to enjoy them elsewhere. Town planning regulations also are based on a growth concept, and the main method of gaining unearned increments revolves about manipulation of land use and re-zoning for more intensive occupation and consequent profits. As a nation we have little regard for the land itself, except for its short-term gains. Such a libertarian policy would not be permitted in most other countries with an economy as advanced as our own.

Migrants from European nations are still regarded as second-class citizens, but the countries they have left have always evidenced a reverence for the landscape and a quality of life. We talk about the beauty of our land, and proceed to butcher its unique but fragile ecology with overdevelopment, both in the country and city, for the sake of a quick and dubious dollar. By contrast, a train journey from Paris to Vienna reveals landscapes almost identical with those that Brueghel painted in the Middle Ages. Even farming methods remain largely unchanged. To fly over England is to discover a whole landscape that is still, in large measure, one enormous garden. It must be admitted that there are many undemocratic reasons for the retention of Europe's rural qualities that involve hereditary privilege and enormous land holdings. The liberty that our democracy permits requires a responsibility which many Australians are not prepared to face. They would rather let American and other multinational interests exploit it immediately, than have a long-range policy for national survival.

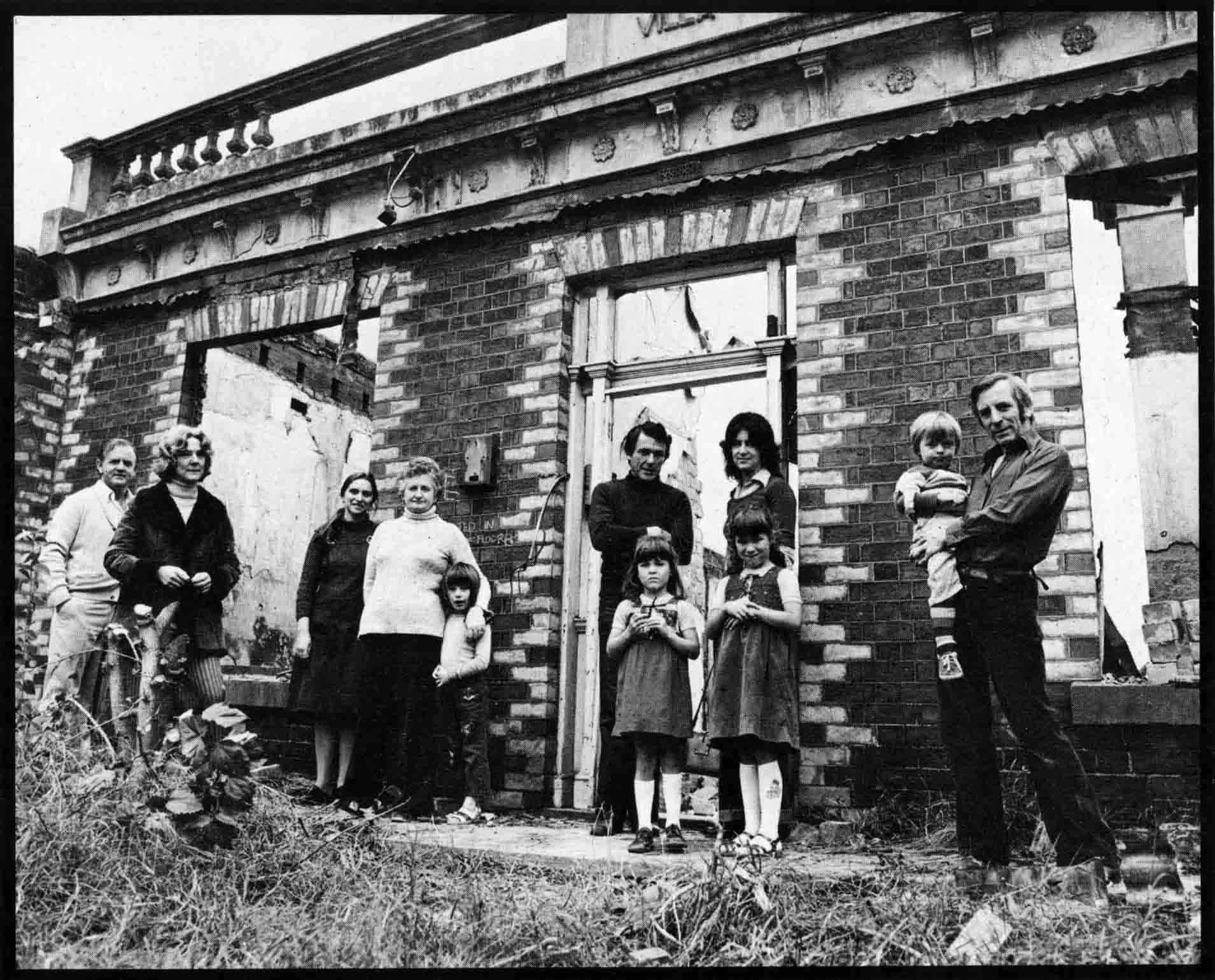

The protesters on the subject land after winning the second appeal (from left to right): Ian Cleghorn, Barbara Flynn, Shirley Pinnell, Pat McIntosh, Gemma Pinnell, John McInerey and family, James and Ron Pinnell

The protesters on the subject land after winning the second appeal (from left to right): Ian Cleghorn, Barbara Flynn, Shirley Pinnell, Pat McIntosh, Gemma Pinnell, John McInerey and family, James and Ron Pinnell

I explained to the Pinnells that they had an arduous three months ahead of them, getting adjacent residents to sign objection forms and lobbying the local council. The mention of the council caused their faces to fall.

'The council will do nothing to help', they said. 'They have a bad reputation.' Nevertheless, I pointed out they must confront them with at least four dozen flaming eyeballs if they wanted to alter them.

'Start lobbying and you will find they are much more cooperative than you imagine. If they are obstructive, then your personal presence will do more than anything else to bring about a new climate. Local government is as good as the local interest in it. If it is commercially dominated, it will be a commercial council. If it is interested in exploiting land, there will be a plethora of land developers and estate agents involved. If people want to change the structure of their council, they must stand for election on it.' The Pinnells pointed out the problem of a young family and many other factors which made this a hard course of action for them, but they went away imbued with a method for winning their case and saving the community of South Burnley. After considerable discussion, they became aware that they had the capacity to win, if they took a real interest in the case and fought for their beliefs.

Australia has become a money-mad country. The opposition to their proposals would come from demented men who had never considered it reasonable that people should come before profit. But the Pinnells and Barbara Flynn believed they personally were placed in the district and among these residents because they knew them and had come to know their hopes and aspirations face-to-face. It was not until the end of January that I saw them again. My suntan from a beach holiday had not started to peel, and the summer season was still in its prime. All it required was for the kids to go back to school and life would be calm and equable again . . . except for those subterranean issues such as South Burnley . You knew that you would really have to get down to spending time and energy on these sorts of problems. The nicest part was the fact that it was entirely voluntary and unpaid. The most difficult was that our people would have to be coached, and our arguments had to be well researched and presented. In tribunals the growth concept predominates and the developer enters the arena as the reigning champion. If you don't agree with his proposal, you are officially called an 'objector', a term which instinctively implies a feeling of being the underdog, a socialist or worse.

They called a meeting of interested residents in the parish hall. There was a good attendance. All were informed of the requirements of defence, and Shirley and Barbara were elected spokeswomen. Their concern for this community was impressive. They had a regard for each other and now they were drawn together by a common threat. All we had to do was resolve and coordinate their individual thoughts into a united front in word and deed.

There is a fairly simple recipe for social action in Australia. It consists of a mixture of 50% passionate belief and 50% cold logic, plus the addition of at least forty-eight flaming eyeballs. Seventy-two would be even better (or twelve extra people). If one of them were blind in one eye, it would not matter. Seventy-one would still be enough.

As a result of our perseverance and planning, the council refused the permit and the developer appealed to the tribunal. The fight was now in earnest. We then prepared a videotape of the whole area, showing all the territory in question, instead of having to visualise it from maps and words. I persuaded them to employ a town planner, not because he could really do anything at the tribunal, but because the residents would have to payout some money. There is nothing like investing in a cause to increase commitment.

It was gratifying to see the appeals boardroom full on the day of the hearing. The residents had learnt their lessons well. They filed in and took up all the gallery seating while Shirley, Barbara and I, together with the planner, took up our positions in front. The council had employed a Queen's Counsel to defend their position in the matter. This learned gentleman, flanked by an assistant, led off and made the usual professional noises. His technical explanations were accurate, but lacking in personal passion. After he finished, Shirley was called to the bar. The video was set up by one of our helpers, a school teacher, who had prepared it. At the signs of the first picture, a new light spread over the faces of the three members of the tribunal. Shirley moved from point to point on cue with the pictures. All her arguments were cogent and professional. The group had done a thorough survey of every house and child, comparing unit numbers with private dwellings. The seventy-two flaming eyeballs silently continued to search the faces of the members of the tribunal. I followed with an explanation of how the regulations and laws so often protect people with money, more than those without it. Here was a viable community satisfied with its lot, which was about to be destroyed by one person for the sake of quick profit. If the position were left unchallenged, he would win. Democratic principles survive only to the degree they are fought for. These principles can rebound on the manipulators as well as support them. The real problem is that the poor cannot afford professional services in the way that the wealthy are able to, nor can they often afford the time.

It became palpably obvious that there are many developers, who might even be well-intentioned, but there was only one South Burnley - one contented community amid a maelstrom of discontented ones. Planners are desperately fighting to develop such communities, and nearly always with negative results. Regulations cannot encompass the feelings of the heart. At best they are a feeble substitute; at worst an ill-considered answer generated by experts who will not understand human problems because they have been retained by the developers.

The uninviting right-of-way adjoining a previous unit development

The uninviting right-of-way adjoining a previous unit development

The Pinnell's tiny front yard - a place for children to play in

The Pinnell's tiny front yard - a place for children to play in

|

Professionals are supposed to supply their services for the good of humanity. Remuneration, if any, should be the result of the quality of the services. The sad truth of our Western. society is that the only certain fact of professional assistance is the bill that follows it. In the case of the medical profession or the barrister, it can sometimes actually precede the service! So often their opinion of what people want or think they want is separated from reality. It was apparent that true communications only come into focus when the persons most affected stand up and do the communicating themselves.

By the time Shirley and I had finished, I was aware that we had won. The opposition said little, feeling likewise. Actually their spokesman said later on that they would have had to take him home in an armoured car if the verdict had gone in his favour. The tribunal retired for ten minutes and, after a long preamble, the chairman found in favour of the residents. He appeared a little confused that there was not to be a change, as if he thought change must come about if society were to advance. The perpetual weighing up of cogent argument can make us insensitive to plain facts. The poor find it hard to keep the professionals in the manner to which they have become accustomed, so lawyers are mostly retained by the rich. As the majority of Australians have a surfeit of possessions, they also find it hard to extend a helping hand to by-passed social groups. Democracy is harder for the poor, but it is sweet when its circuitous perambulations produce just results and right is done. Solzhenitsyn said with prophetic insight, 'We can lose democracy because nobody is prepared to die for it'.

Winning was one thing; maintaining a winning position another. The local council had been used to things going very much their way for years because so many residents were not aware of their rights and responsibilities. It was now necessary to press home the advantage freshly attained on the field of battle. This commenced at the next community meeting. The name of the association became the South Burnley Golden Mile Residents' Group. This made everyone feel good and radiated a sense of well-being. The district had had a more elegant past. It was now about to be reinstated, if only in a minor key. But there was a real sense of revival within it too. 'We used to just say "Good morning" to each other', one old lady commented, 'but now we stop and talk'.

Our town planning friend drew a suggested residential code for the area. This was far too humble and deferential, as if he were so conditioned by development that he did not know how to reverse the position either.

I interested John McInerney, the Planning Officer for the City of Heidelberg, in the case and he accompanied me to some of the meetings to help determine the next step. He gave the local residents some advice and then Shirley, Ron, Barbara and others wrote their own code. They appeared before the council committee and put their case. The councillors were listening hard and thinking co-operatively by this time. The residents soon received a letter thanking them for their excellent work and stating that the council intended shortly to employ an expert to draw up the town planning proposals. No doubt this proposal was well-intentioned, but my warning to the Pinnells was that good intentions do not necessarily mean good planning. A poetic balance between the spiritual and the technical has to be maintained at all times. Passionate belief and cold logic may be strange bedfellows, but they produce democratic results in the end.

We all realised that the frustrated developer would make a further attack on this citadel of profit, which in due course he did. It was more modest, but was still exploitive of the existing population. The council still did not know how to act objectively and in the interests of the majority. At the end of twelve months, the whole matter was still in a state of flux, but by this time the leader of the State Opposition had weighed. in on the side of the people. It was fascinating to watch the unfolding struggle between local interests and outside exploitation. The price of democracy is the same as it has always been: eternal vigilance.

In time we found ourselves once more at the tribunal fighting the cause of 'life in the city' versus 'profit for the individual'. I was not overoptimistic in this instance. The committee had done a good job once more, but objections tend to look stale the second time around. When we finally heard we had won the appeal, I found it hard to believe. At the time of writing the little old ladies with the flaming eyeballs are resting in peace.

< Previous Book

< Previous Chapter

:

Next Chapter >

Next Book >